IYKYK: The Currency of Connection

By: Scott Luther

It’s real: strangers are judging you.

Are you with us: “Have you ever noticed…” and “OMG I thought I was the only one…” are the twin drivers of seeking belonging.

While: “Can you imagine…” and ridicule (on a spectrum from puzzlement to mean-spirited) are the equal-and-opposite forces forging connection on social.

Find your people

One of the original promises of the internet was helping people find their people.

An ideal as old as calling the internet “the information superhighway”: No matter what you are into, no matter how obscure or how far-flung people who share that interest might be, the internet can help bring you together over a shared passion.

As much as we may have gotten wrong about the idyllic and romantic visions of the early web – and in particular, the early ideals of the social web – the ability for people to find their people online still rings true.

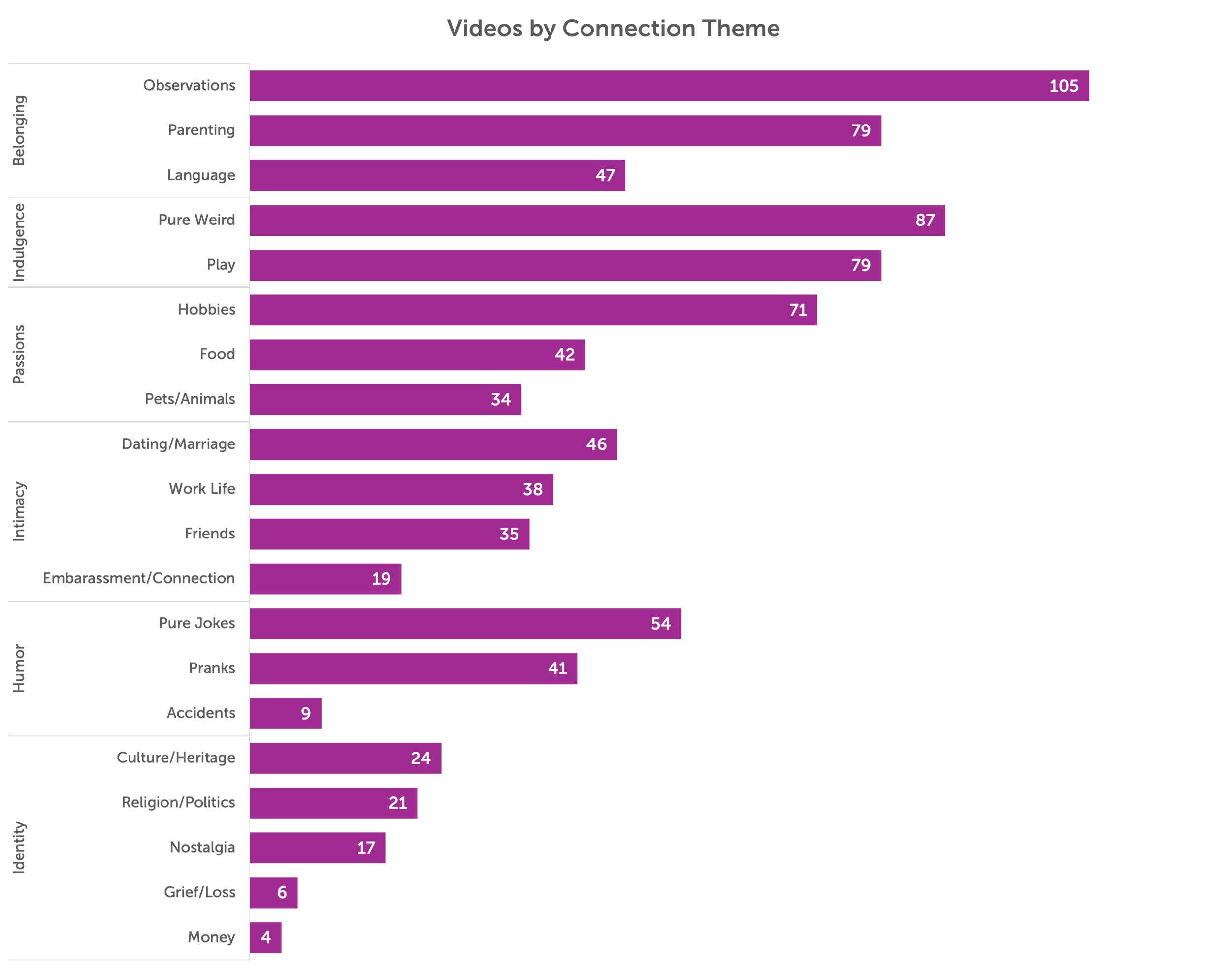

What we’ve learned along the ways is that finding connection takes many forms.

In some cases, it’s simply feeling seen – someone takes the leap and shares an observation: “have you ever noticed…?” sparking the reaction “I thought I was the only one!” and you feel validated. That observation could be anything. Revealing the “bits” you do to bring yourself some moments of levity in a day. Puns. Observations about how you grew up, seemingly strange habits of your parents. Realizing all the apocryphal stories about aging are cruelly true.

That simple feeling of there’s someone else out there like me is comforting.

There’s another level of finding your people that can be found through social content – instead of feeling seen, you find yourself belonging.

Belonging gets created by joining the in-crowd – when “one of US” becomes real, when you finally find yourself on the inside of the If-You-Know-You-Know (IYKYK) circle. Modern social media – the algorithmic curation and acceleration of memes – has supercharged the potential of IYKYK-based-belonging. For good and for bad. The good is obvious: in an age of increasing isolation and a loneliness crisis, any route to connection has profound benefits.

The bad has a few parts too. IYKYK in-groups can calcify into filter bubbles and echo chambers, shrinking the world of those on the inside. Recycled jokes, singular worldviews, and a host of -isms can fester. And that’s what leads to the second part of the bad: in order for there to be an in-group, you’re by definition creating an out-group. Belonging has the potential to beget Othering. It’s a universal human experience that’s been a staple of comedians for decades, bonding over mutual annoyance, complaining about your boss/co-worker/petty inconveniences/nemesis/the person in the group chat that’s not in the other group chat/significant other/teacher’s pet and all the sudden it turns into all the people who aren’t like us. And you know what? It feels good. You’re on the inside.

This isn’t inevitable. Nor is it the universal truth of social. But it is a risk behind the simple fun that much of the “Weird and Wonderful” we come across on social, it requires a discerning and empathetic eye to judge whether observations and revelations are made with good intentions or ill (even if unintended) will.

That the internet, and social in particular, can have harmful effects on individuals and social dynamics not a shocking revelation.

The sociological, psychological, political, and economic effects can be better explored and explained through other means. What this study helped us realize is that (1) social can absolutely still help realize the original promise of connection and belonging, in both simple and profound ways, and (2) that even the most lighthearted, seemingly innocuous observations and self-reflection can have unintended consequences for Othering.